I never keep more than one box of cereal in my apartment at a time. In the early morning it’s easiest to make the routine as streamlined as possible. There are hundreds of more important decisions I need to make during a normal day, especially when the only two cereals I buy are Grape Nuts and some off-brand alternative that might as well be Grape Nuts.

The newest episode of Black Mirror premiered on Netflix recently, with an entire story revolving around decisions directly made by the audience. While not the start of a new season, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch continues the series obsession with how technology influences our daily lives. It is not the first piece of interactive television that the streaming service has released, but it is the most notable. For better or worse, Black Mirror has become one of the most prolific, culture-defining shows of the 21st century. Having its creator, Charlie Brooker, embrace the concept is a significant indicator of where the future of television might be heading. For an idea so monumental, it seemed fitting that the first decision to be made in Bandersnatch is choosing between two different brands of cereal.

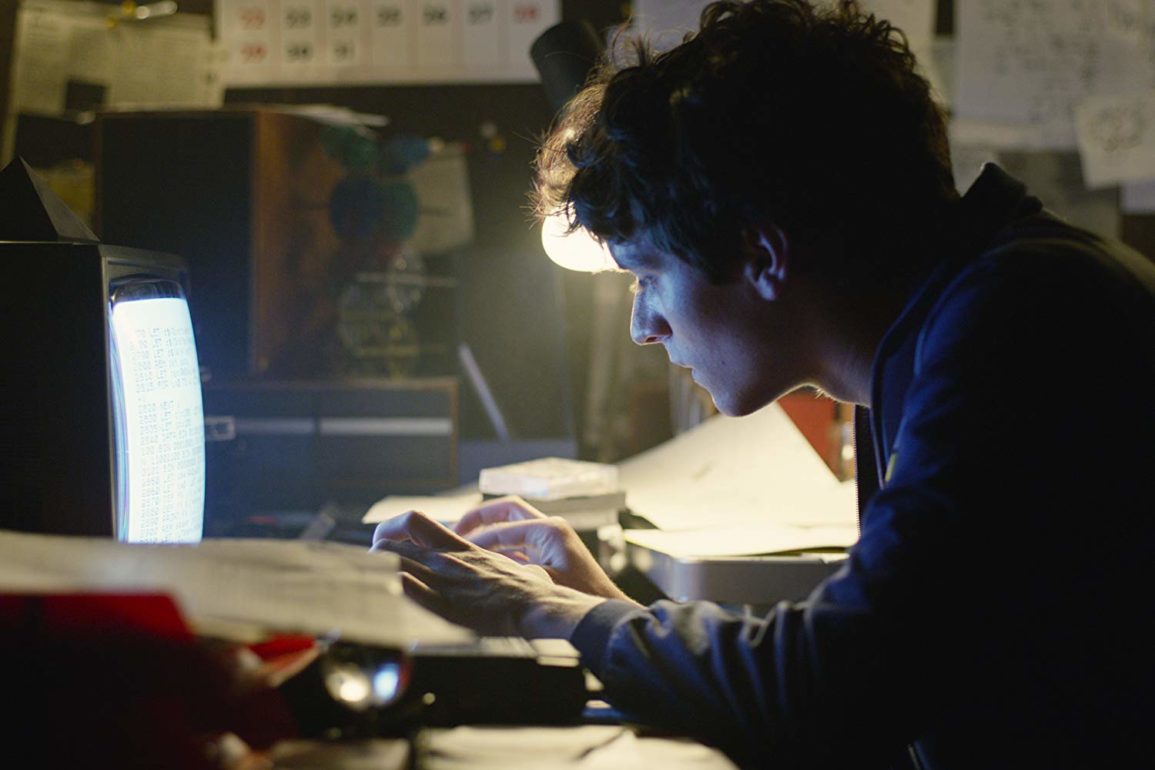

The audience avatar is Stefan Butler, played by a neurotic Fionn Whitehead. Stefan is a programmer in 1984 coding a video game adapted from his favorite “choose your own adventure” book, Bandersnatch. The idea is ambitious, video games at that time were usually never more than a simple, straightforward premise. Having the forethought and the patience to program hundreds of pathways is a tall order. The work tests Stefan’s psyche. After a session with a persistent therapist, Stefan reveals a childhood trauma that might show why he’s not been in a normal mental state, for years. All this is exacerbated further by the continual choices made for him, through force of will be the viewer.

With every decision, Stefan’s paranoia magnifies. He slowly becomes more self-aware that some outside entity is making his decisions for him. The story and setting fit snugly in Brooker’s wheelhouse. He has an innate talent for portraying paranoia and technological dread. He is also a savant a when it comes to constructing highly detailed, expertly crafted ‘80s environments. Here he has Netflix subscribers controlling every aspect of Stefan’s life: from the aforementioned cereal dilemma, to shopping for vinyl and even deciding just which synth-pop cassette to put in his Walkman. While Bandersnatch does make a direct reference to the Black Mirror episode Metalhead (David Slade directed both installments), aesthetically it’s more reminiscent to San Junipero.

Critiquing interactive television is challenging in and of itself because each course through Bandersnatch is a unique, inherently personal experience. Television already induces different emotional responses from its audience, but never before has a story actively shifted and transformed based on an audience’s split second decisions.

The best course (at least upon first watch) is to recognize plot points when as they appear, attempting at all costs to avoid dead ends. Some are rather obvious, others are not. Suffice to say, pouring tea on Stefan’s computer at every possible opportunity is not the most efficient way through Bandersnatch, no matter how cathartic it might be. Part of Black Mirror’s appeal is having the “If I were him, I would have…” discussion after every run. Bandersnatch allows that dream to come true. There are multiple endings to the special, but there is one classic “Black Mirror” finale, as perfectly profound and melancholy as several more traditional episodes.

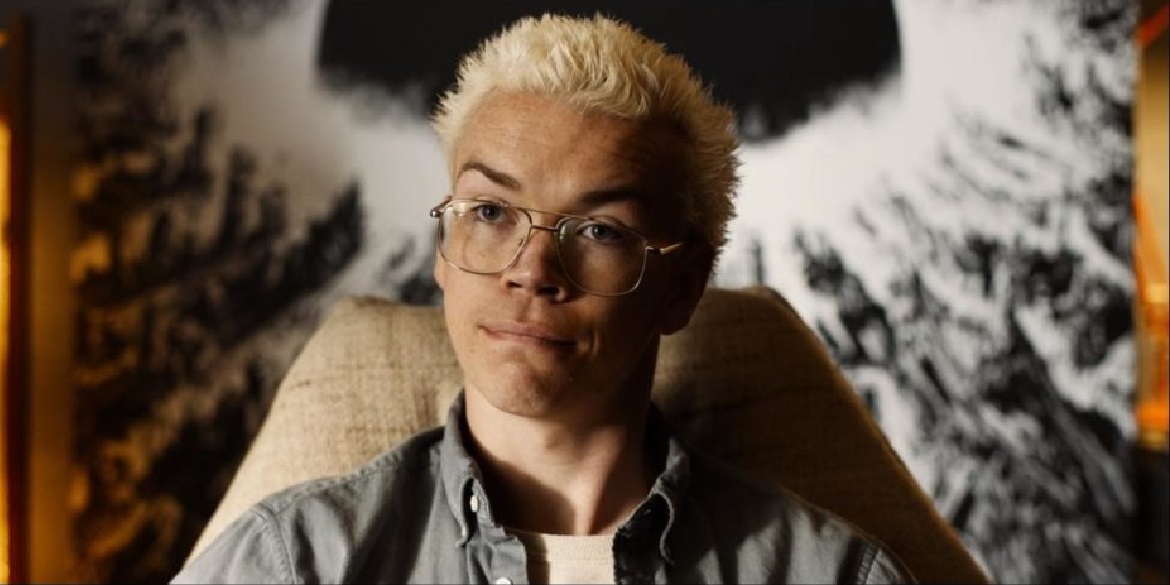

In the middle of this is the bizarre Colin Ritman (Will Poulter), an expert programmer and only person who understands the genius needed for a concept game in the 80’s. He also jump starts Stefan’s paranoia during an acid trip, bringing up government conspiracies, alternate timelines, and time travel. There are a few hints that Colin has an eerie awareness of exactly what is happening, but he doesn’t stay around long enough for the idea to be carried through. The latter half of Bandersnatch becomes too muddled and busy with decisions to include Colin.

This missed opportunity leads into the episode’s most glaring flaw, which happens to be how the audience becomes an actual character. The decision making within Bandersnatch at first looks like a creative way for the audience to embody the lead character, thereby fully immersing themselves in the story. On several occasions, especially in the beginning, the camera shifts to first-person view, like a video game, so the audience can directly face the consequences of their choices.

However, as Stefan becomes more self-aware of an outside force, the audience detaches themselves from the protagonist and instead becomes that outside force. There are even a few funny and jarring paths that break the fourth wall so audaciously they’d likely make Deadpool blush.

As the audience becomes a character, it quickly shuts down any mystery involved with Stefan’s situation. Here it’s much easier to go off the rails, because there’s less investment in the lead’s well being. This leads to Bandersnatch essentially becoming more work than entertainment. At this point, all the audience can do is wade through Stefan’s unraveled mind until the finish line is revealed.

A second viewing is best for looking into all of the nooks and crannies in the story. Brooker rewards curious rewatchers with the addition of hidden easter eggs. Through practically every scenario we see how Stefan’s decisions affect the actual Bandersnatch video game he’s making. There’s a dedicated video game critic on the local news, serving as a barometer of how good actual game turns out. Most paths end in a disappointing or lackluster review, but there is one path that leads to a perfect five stars.

Brooker and Slade make obvious parallels to the episode itself as an ambitious, maddening undertaking. A character goes so far to reference the “choose your own adventure” idea as “the illusion of free will, but I decide the ending.” The illusion of free will might be entertaining in concept, but once it’s realized as an illusion it doesn’t quite make for a fulfilling piece of television. Though the true ending is worth the wait, it does feel somewhat exhausting, after all the runs it takes to get there. It’s impossible not to think of what Bandersnatch might have been as a normal episode of Black Mirror.

Also difficult is imagining a story concept more aptly suited for interactive television. Brooker doesn’t shy away from how meta Bandersnatch becomes. The process and the plot are tightly intertwined. As a story on its own Bandersnatch is a well told conspiracy thriller. It’s nowhere near the worst Black Mirror episode (shoutout The Waldo Moment), but it also doesn’t deserve a spot in the upper echelon. The interactive format is bold, yet fails to execute its primary goal, which is to further audience immersion. The more interesting conversation instead is what this could mean for the future of television.

Black Mirror’s anthology format allows the show to be as creative as possible in each episode. Interactive television is still in the experimental stages because it is so difficult and jarring to simply meld with established shows. Stranger Things can’t shift into interactive format on Episode 5 and shift back in Episode 6.

Bandersnatch might be more of a video game than a film or television episode, but the lines of these mediums will continue to be blurred in the future. Most TV seasons are written and watched like 10 hour movies. Most modern video games have twenty minute cut scenes between actual gameplay. Streaming services have revolutionized how the modern world receives content, but Bandersnatch is a pioneer in how the modern world interacts with content.

As virtual reality and interactivity becomes more advanced, the three mediums might eventually become one. This might be years or decades away, but what is a Black Mirror review without a little dive down a technological rabbit hole?