Painting, as an artform has often been the subject if many of a movie. Painting, as an act, less so. Maybe it’s because viewing and accessing a final work, rather than the process, allows people to engage more with the art work on display. It’s a strange divide. There’s endless films about the struggle of an artist, but not necessarily dedicated to why the body of work of that said artist is important. That abstract detail is something that The Last Vermeer also balks at, simply yelling about importance willy-nilly, in hopes of keeping the audience awake. It’s the cinematic equivalent of watching someone trying to use a card catalogue to find a rare book, plucking the card and the promptly setting the building on fire. You understand what you’ve seen, even if you aren’t sure what any of it means.

In 1945, weeks after the fall of Adolf Hitler, a division of the Allied Forces investigates artwork in Nazi possession. Those charged with the crime of assisting sympathisers and co-horts, are shot in the street as an example. Hundreds of paintings and various objects of great wealth clutter a makeshift office. In the hopes of being returned to their rightful owner. One day, a stunning piece by Johannes Vermeer catches the eye of Captain Joseph Piller (Claes Bang). Only recently discovered, it turns out the painting had been sold to none other than Hermann Göring. Upon discovering a note hidden in the frame of the painting, Piller is pointed in the direction of the flamboyant Hans van Meegeren (Guy Pearce).

Is van Meegeren a Nazi sympathiser or something else? Did he profit off death and the eradication of a people? As quick as Pillersets his ducks in a row, a series of events calls everything into question. As a man of Jewish faith, who turned to the resistance in the war, Piller is conflicted. He harbors resentment for his wife, who cavorted with Nazi officers. He’s prone to bursts of anger and prejudgment. Sensing a desire for justice at any costs, he hides van Meegeren away. In hopes of protecting the criminal, as he chips away at a greater mystery looming overhead. Aided by former fellow resistance member Esper Dekker (Rolland Moller) and assistant Minna Holmberg (Vicky Krieps), Piller and company stumble onto a truth that’s stranger than fiction. As long as you haven’t read up any history associated with the facts here.

Early on, all the pieces exist for The Last Vermeer to be a crackling post war tale of intrigue, escapades and derring-do. In spurts it gets there. For the most part though the film is a plodding mess. Jumping haphazardly from one story element to another. Filled with lapses in logic and changes to history that seem rather silly. Something undoubtedly common on “based on a true story” works, but here it’s distracting, instead of engaging. As ridiculous as things may be in the moment (partially due some of the most restrained melodramatic acting imaginable), the overall film never finds a way to open that vein and give the proceedings extra life. If Ford v Ferarri was the platonic idea of a dad film everyone could love, The Last Vermeer

is the dad movie that turns people off the genre all together.

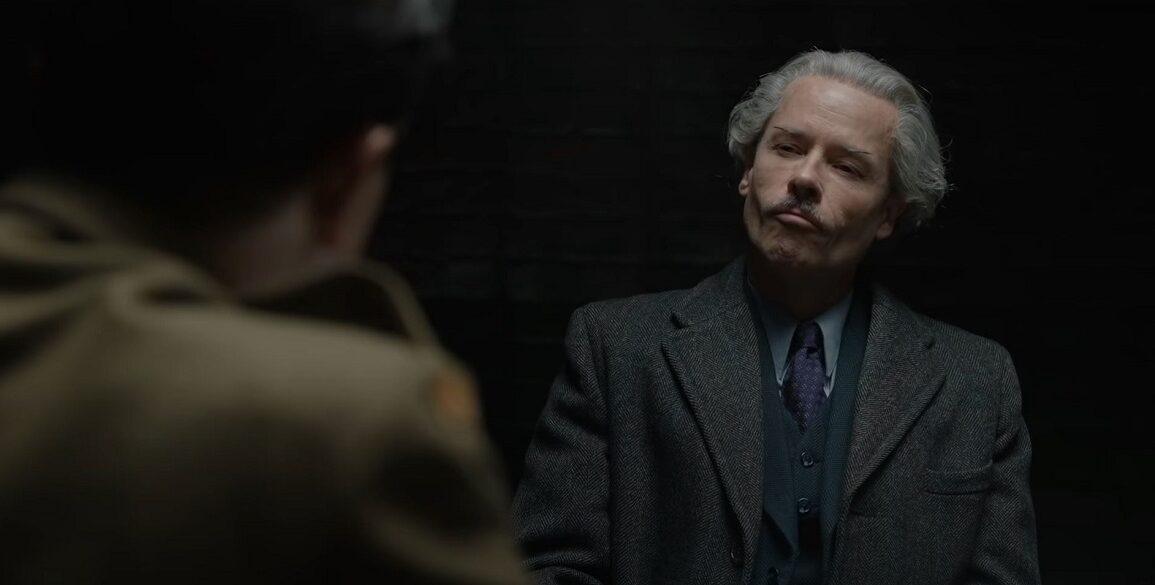

About halfway through the film, it finds a state of clarity (like most of the characters do at the bottom of van Meegeren’s numerous bottles) when it becomes a courtroom drama. It’s mostly unexpected, the ease with which the turn happens. Part of that’s due to a detective story that doesn’t know how to detect. The other element that gives things a jolt, is finally putting a larger focusing on the far more interesting character here: Hans van Meegeren. It takes Pearce literally shackled, golf clapping his hands and stating “finally” to bring the movie alive. When the screen includes Van Meegeren, things perk up and has a sense of purpose and energy to it, that’s lacking elsewhere. Any time it cuts away from Pearce, the movie suffers greatly.

While Piller himself feels like a bland canvas, the film keeps placing more interesting characters around him. Making the focus on him feel stagnate or trying by comparison. Moller continually forges strange friendships with everyone he interacts with and doesn’t throw punches at. From his vague history with Piller to the drinking buddy he finds in Meegeren. As a counterpoint Krieps is solid, if utterly robbed of screentime. A far cry down from the presence she was allowed to exert in Phantom Thread. It’s also a failing of the script which has three women, but doesn’t do much with them. In fact, it doesn’t really know what to do with any of the characters. Setting them in a row and hoping the established beats are enough to keep viewers above a snooze.

As a film about artwork and talent, The Last Vermeer unfortunately adapts a workman approach. As opposed to one with verve or vision. Sets and cinematography fundamentally look fine. Actors carry themselves nobly. Yet the story execution around it all falters. A movie is only as good as the one steering the ship and Dan Friedkin, in his directorial debut, isn’t necessarily up to the task. Events take far too long to get going, as almost an hour elapses before the film kicks into high gear. Spinning it’s wheel before then, as a way of approximating motion. Friedkin, the producer of several successful films, understands the hallmarks and beats of a great film. He just isn’t fully sure how to capture that magic himself. That his script comes from the people responsible for Anonymous and Cowboys & Aliens (John Orloff and Mark Fergus) doesn’t do him any favors, either.

For all the blistering and rampant negativity, The Last Vermeer never falls into the category of a truly bad film. Much like all art, it’s sure to find it’s band of supporters and admirers. Others though will notice and wrestle with the inherent frustrations and walk away shrugging their shoulders. There’s nothing here to set it apart from the multitudes of other middle-of-the-road films, that focus on the exploits of WWII. They may not raise the questions a film The Last Vermeer raises, but has no intention of asking and are all the better for it. As far as middling entertainment goes, it’s a “meh”overall. Those who may be astonished and impressed by van Meegeren’s personality, are better suited by seeking out F For Fake by Orson Welles. All others just visit a local museum, in order to have a more thrilling and historically enriching time.