Few budding filmmakers have the start that Ted Geoghegan received when he made We Are Still Here. Coming from the publicity end of the industry (though he had done some screenwriting years before), it seemed like a lark. That film garnered a ton of goodwill and great press in the festival circuit, before landing on several streaming platforms. His sophmore effort, Mowhawk, sees him swinging for the fences, armed with both good intentions and personal politics. Unfortunately he falls into the same trap that normally befalls such films.

In 1814, the war of 1812 still rages on, though the Mohawk Indians have manages to stay neutral up to this point. A British envoy, Joshua (Eamon Farren) warns the tribe that American troops plan . He offers help in the form of weapons and the backing of Red Coat . It’s hard to discern how long Joshua has been among the Mohawk, but it’s long enough to gain the trust of 2 younger members, Calvin (Justin Rain) and Oak (Kaniehtiio Horn). Enough time has also passed, in that the 3 have entered into a polyamorous relationship.

While the elders of the tribe are hesitant to act, Calvin makes a bold gambit, setting fire to a nearby camp of American soldiers. Unknown to him, a few survivors give chase, wanting to exact revenge. What follows is a rather rudimentary tale with a few wrinkles. The soldiers, however wronged they may be, are very much the aggressors. Their belief in “justice” tips the scales and a chase takes off across the wooded landscape.

The band of weary soldiers, doesn’t feel so much like survivors of a terrible ordeal, but more like a rag-tag outfit left behind. Commanding Officer Holt (Ezra Buzzington) rules with an iron fist. Myles (Ian Colletti) is a young hot-head and Lachlan (Jon Huber) a quiet giant. Fancy lad Yancy (Noah Segan) is the best actor in the bunch and for it, he’s relegated to a thankless role of interpreter, of sorts. There’s a sniper, whose overly distracting spectacles define his entire character.

From a technical standpoint, Mohawk impresses, covering up a scant budget. Save for a few bits in processing, the cinematography sparkles, capturing the denseness of the forest. There’s no mistaking this with The Revenant

, but what’s on display gives the film a wide open look. Wojciech Golczewski provides a sparse synth score, elevating the tension, when it occasionally ramps up.

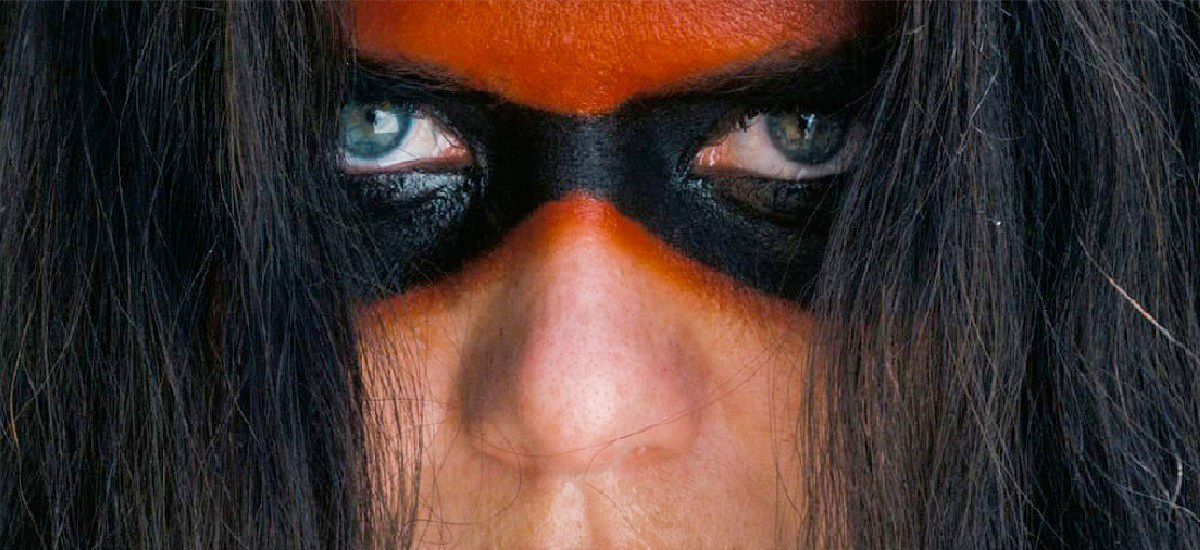

Mohawk‘s highlight is actually it’s ostensible lead, Kaniehtiio Horn, thought that isn’t readily apparent. Her eyes pierce the screen, constantly commanding, even when others share the frame. Geoghegan doesn’t lean into this enough, instead diverting attention to less interesting characters. Horn’s presence is enough to see the film, but where other films would lean into her emerging strength, here they cut away.

The other actor’s are a mixed bag, an issue that at times also plagued We Are Still Here. As much stability as someone such as Noah Segan can provide, the rest of the American soldiers chew scenery that isn’t even present. Holt in particular seems transplanted from a Shakespearean drama. Better served is Jon Huber, more famously known as Luke Harper from the WWE. While given little to do, he at least cuts an empathetic character, among cruel, humorless men.

Mohawk is ambitious. Ted Geoghegan and Gary Hendrix have made something different, however uneven it may be. That in and of itself is commendable. The problems lie both in execution and a conflict of tones. Having a message underlie your film is a great touch, unless it clashes violently with the natural direction the story wants to gravitate in. Mysticism pokes it’s head into the proceedings, but never gets the focus it needs. In a way, that aspect seems shoehorned in, given the title of the film. It would be an egregious (almost racist) oversight, were it not the part of the film that wins the honor. Geoghegan’s political-ness is ultimately what sinks the film. Or at least the way in which it is implemented. Character’s monologue or preach, when silence or stillness would be better suited. Allegory can easily be conveyed without subtext being rendered literal text.

Most directors spend the better part of their careers, if not all of it, bemoaning the missed opportunities to make their “grand opus”. At the same time, holding out until they have the budget to meet their visions should enter into the equation. Desire can do strange things to those who feel they must act only in the moment presented to them. For all the strengths Mohawk has on display, lack of restraint is its undoing. That’s unfortunate, because as muddled as the film may be, it’s captivating while it transpires. Even if that praise is mostly confined to the cinematography and allure of Horn’s performance.