When most people think of older actors, they unfortunately regulate them to wise or doddering grandfatherly roles. Almost wanting to constantly lash out at those individuals, Richard Gere has spent a little over a decade making sure that people understand that he has a wealth of talent to go along with his good looks. Thankfully, not only does Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer, put him in a film with one of the longest titles ever, it also dutifully places another well earned feather in his cap.

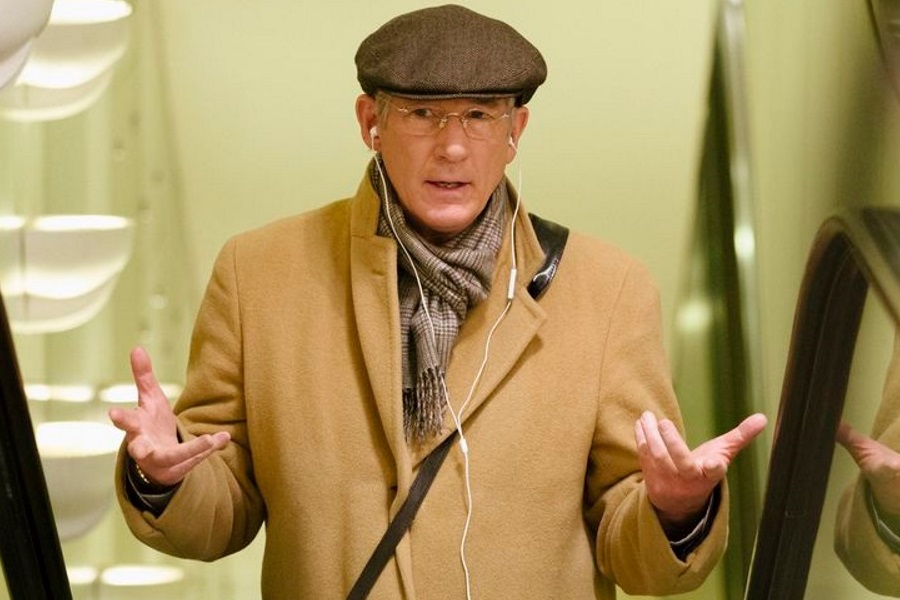

Norman Oppenheimer (Gere) is a fixer, the guy who wants to help influential people get in touch with other influential people. Always adorned in tan camel coat, plaid Gatsby cap and iPhone earbuds dangling around his neck, he’s a mover, but not really a shaker. He claims to know everyone through 3rd or 4th degrees of separation, just enough to insinuate connection without incriminating himself. Surprisingly, his drive isn’t wealth, rather he wishes to be the man behind the man that gets thing done. Simply being invited into a room of powerful people who know his name is enough.

Norman just might be the best performance of Richard Gere’s career. Nothing he does is showy or distracting. He embodies a character that is as richly layered as it is basically hollow. That’s not a slight in the least, as it’s essential to the character. Perhaps the most astonishing fact about the way Gere portrays this man is that he emphasizes his meekness. This isn’t an individual given to big boisterous proclamations. Instead, he is a lonely, pathetic, but kindhearted soul. The phrase he asks to everyone he meets is, “What can I do to help you?” It’s a shrewd tactic, if not for the fact that he entirely means it. He gets to do something that he thinks will make a powerful individual want to help him out in the future. He’s too naive and hopeful for a world of cuthroat individuals. The film is divided into four acts, recalling Greek tragedies of old, readying the audience for what’s to come. Norman is clawing his way through whatever piddly information he can find about powerful moguls through his lawyer newphew (Michael Sheen, playing a character that is 70% reaction shots and killing it.) When failure comes sooner than expected, he switches to the next nearest avenue to reach the mountain top.

The film is divided into four acts, recalling Greek tragedies of old, readying the audience for what’s to come. Norman is clawing his way through whatever piddly information he can find about powerful moguls through his lawyer newphew (Michael Sheen, playing a character that is 70% reaction shots and killing it.) When failure comes sooner than expected, he switches to the next nearest avenue to reach the mountain top.

Through happenstance (basically stalking) he is able to befriend the deputy to the deputy to the Prime Minister, Micha Eshel (Lior Ashkenazi). Norman makes the outrageous gesture of buying the man some shoes in the hope that he’ll return the favor by coming to the dinner a wealthy businessman (Josh Charles) is throwing. Three years pass and that simple act ends up changing both men significantly when they cross paths again.

What’s astonishing is the way writer-director Joseph Cedar surrounds Norman with other interesting, but somewhat empty vessels. It skirts the normal definition of what constitutes a one, two or three dimensional character, both given the story that’s being told and that they’re more or less props in a larger game at play. The irony, of course, is that Norman himself is oblivious to that same game.

Chief among this lot is the future Micha Eshel. Subtle hints litter the film that Micha may be the ying to Norman’s yang. Each of the men want to be a part of history, for people to tell stories of the great things they’ve accomplished. They’re seperated by two main elements on their journey: Micha has bigger goals (Norman is happy if people acknowledge him) and understands how to successfully manipulate people into helping him. They’re both false fronts who are obsessed with an ideal that most others may laugh at. It could be easy to dismiss their similarities, were the film not willing to point them out. Cedar allows only Micha extra screentime away from Norman, giving bigger insight into the two men being different sides of the same coin.

At the heart of it all is a farcical parable, but only because it lacks a discernible bite that satire often requires. If the film had loftier aspirations, this could be seen as a demerit. As it stands, it allows a warmth to radiate from Norman, even as everything starts to close in on him. The world that everyone inhabits feels as if it belongs in Being There

or the works of Preston Sturges.

To keep such a simple, yet far reaching movie close to the ground, Norman finds inventive ways to pull the audience’s attention. Most films dream of the ability to blend different facets with the ease in which cinematographer Yaron Schraf, editor Brain K. Yates and the production duo of Arad Sawat & Kalina Ivanov work together. Deciding to eschew the normal passage of a montage, they condense the frame through brilliant design, so that people who are across a city, or even the world, feel as if they are just feet from each other. Doing so heightens the theatricality that’s inherent in the work. It’s a deft move, taking the mundane and making it feel alive, while staying just this side of fantasy.

Norman may not be the world’s greatest film in the end, but that’s perfectly fine. It’s a character study anchored by two balanced and fully realized performances from Richard Gere and Lior Ashkenazi. Those looking for decidedly pointed commentary or truly deep meaning may be left wanting or turned off by the seemingly tidy resolution. Joseph Cedar has crafted a beautiful and quaint film, the kind that usually get sidetracked by wanting too much for it to be a box office success. Much like Norman himself, the film has no intentions of chasing the elusive dollar, instead surviving on the hope of just being remembered.