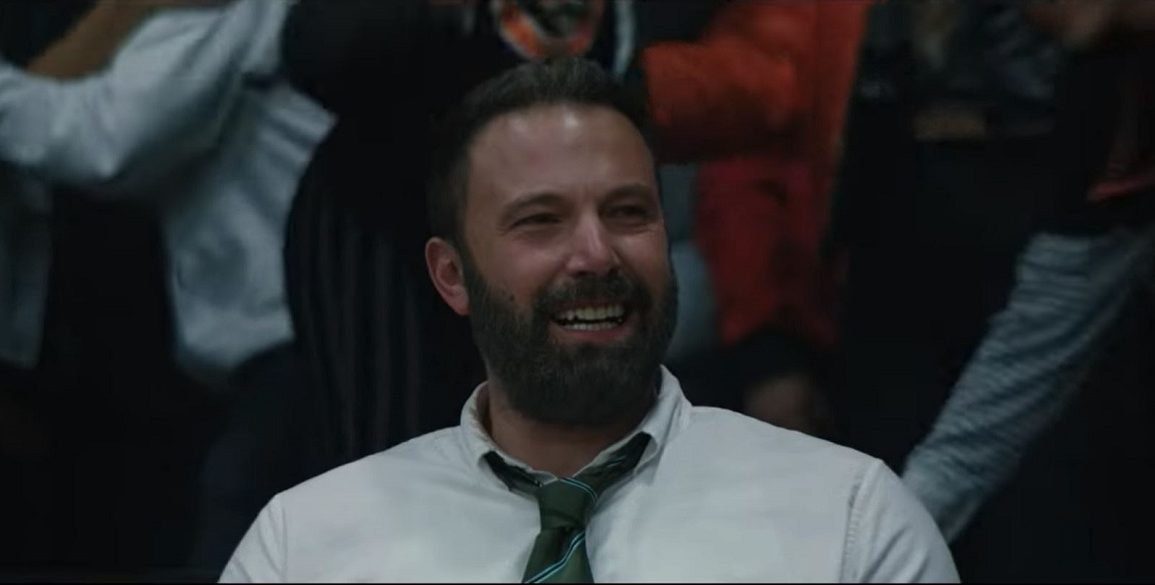

Like it or not, audiences walk into a sports movie with a certain set of expectations. There should be a scrappy, underdog team, a training montage, and at least one buzzer beating play. Gavin O’Connor doesn’t shy away from these tropes in The Way Back, he leans in. His most on-the-nose decision here also happens to be his best, which was to cast Ben Affleck as his lead. In a genre that is often full of clichés and empty speeches, The Way Back manages to find sincerity and honest forgiveness. Some of that truth is in the script, but most of it is found in the raw emotion of Ben Affleck.

Jack Cunningham (Affleck) is a washed up high school basketball star still living in his hometown. He passes the time at his construction job by sneaking liquor into his steel water bottle. Infrequent meetups with his ex-wife (Janina Gavankar) start amicably until they quickly become strained and resentful. O’Connor directs most of the film with a shaky camera. The technique can represent the frenetic chaos of a high school basketball game, but it more importantly represents Jack’s constant instability.

When the sun goes down, he either kills a case of beer at his house or gets wasted at his favorite local bar, Harold’s Place. Without quoting the entire Cheers theme song, everyone knows Jack Cunningham’s name. A small town atmosphere does provide some support, a man who knew Jack’s father is accustomed to walking Jack home from the bar every night. However, for people dealing with addiction, grief, and regret, a hometown can feel like quicksand.

The varsity basketball coach of Jack’s alma mater resigns due to medical issues, and the school asks him to be the replacement. Jack hasn’t touched a basketball in about twenty years, which was the last time that Bishop Hayes High School put together a competent team.

The current roster is undersized and undisciplined. Scrimmages are a mess and the games are even worse. Like most sports movies, every starter has his own particular quirk. The team’s best shooter starts every road trip by pledging his love to a different classmate. Another player leads a pregame dance circle, even when the team has earned no right to be celebrating that early.

What makes Jack an interesting coach is that he’s far from the militant, no-nonsense Coach Carter type. Instead he picks his battles in a stranger sense, especially when it comes to cursing. That’s because Bishop Hayes is a Catholic school, one that has a strict code of conduct. The most joyful choice that The Way Back makes is that Jack completely disregards every rule against cursing, on and off the court. The team priest (Jeremy Radin) who sits on the bench tries his best, but Jack can’t help himself from dropping every bomb in the book. There is a unique brand of catharsis that is only felt by verbally purging every negative thought onto a referee.

O’Connor tends to focus more on Jack’s sideline tirades more than the actual basketball. Jack turns the program around relatively soon after taking over. Any sports movie student knows that a team is only one montage away from winning a few games. It’s nice to see Jack find passion in something again, though it feels unearned with what’s presented vs what’s left out. The team and Jack never quite feel like one unbreakable unit. The competition and the gameplay are standard for most basketball movies. This isn’t Blue Chips, there aren’t any NBA superstars pretending to be high school kids. One slight exception could be Melvin Gregg, who played an NBA player in Steven Soderbergh’s High Flying Bird.

Other sports movies tend to overextend themselves by providing backstory to each and every player on the team. A lack of focus can detract from the flow and message of the film. A few brief scenes involve the cocky center played by Gregg, but the film gives the most spotlight to the star point guard. Brandon Wilson (Beyond the Lights) is quiet and unassuming, his character’s insecurities stem from his relationship with his father. He’s easily the most talented player, but he never learned to use his voice to lead.

With a life full of regrets, The Way Back places Jack in situations to make positive steps forward. One of those opportunities is to help Brandon fulfill his potential. At the same time the film is absolutely punishing to its main character. O’Connor’s camera doesn’t stray from his star, Affleck allows the audience to be as close and intimate as possible. This style is incredibly effective when it’s showcasing a bonafide movie star who has built a relationship with audiences over decades.

The result of this kind of insularity can be that some topics are mentioned but never properly addressed. The team plays for a Catholic school, but religion is never explicitly involved with the story. The film is still able to effectively portray Christian themes of redemption and forgiveness while avoiding the cliché minefield of quoting scripture. Religion is not a part of Jack’s life, so it’s not a part of the film.

The script also alludes to economic challenges that some players face, Brandon most notably. His father doesn’t attend his games because he doesn’t want his son to believe that basketball is the only path to success. The cultural subtext to that idea is implied but never discussed. If the film was about a basketball team, it would have. The Way Back is about a basketball coach. Brandon’s struggles matter only in relation to how they matter to the coach.

Most people with access to Google know of Affleck’s recent struggles with his personal life. Like Jack Cunningham, he’s also recently divorced and struggling with addiction issues. This story gives Affleck the freeway for his most honest, raw performance in years. The film doesn’t even allow him to access his natural swagger and charisma that has won over audiences for years. For him to tap into a performance like this while being handcuffed is a testament to his talent.

Every sports movie has its clichés, the success of the movie depends on if they are effective or not. With O’Connor’s direction and Affleck’s best performance in years, The Way Back is definitely a success.